Nipped in the Bud is a beautiful, shattering, important and healing show about experiencing and surviving sexual assault.

The exhibit, at the Chase Gallery, Nova Scotia Archives, Halifax, to June 28, should be widely seen and displayed for its message and artistry.

Nova Scotia artist Gillian McCulloch brings her enormous skills at realism and multimedia techniques to over 42 works in a journey from darkness to light, from fear to safety, from depression and anxiety to love in mirrored “self-affirmation” lightboxes.

While I use the term healing, McCulloch says healing from sexual assault is never a given. “You want to live your best life. You want to blossom as best you can,” she says. “I often say to people if you are still here you’re doing well.”

The point of the show is to help “other people to know they are not alone” and to warn parents and teachers about predators. “With the internet it’s too easy.”

McCulloch’s last exhibit at the Chase Gallery, Pandora’s Box, examined depression which she suffered from for years, living in a state of high anxiety with sleepless nights, without knowing why. Then she uncovered an event her mind had blocked out. As a nine-year-old she had been raped by strangers at a party.

The show’s title comes from its first image, a small black and white scratchboard of a broken-off bud on a child’s single bed, an image she did in 1999 “before I knew what was going on. This is the missing piece from the Pandora’s Box show.”

She twins paintings of her nine-year-old self, one as a smiling blond child in a field of flowers, the other as a shut-down, worried child in a blue dress with a dagger – a shattering image and even more shattering for the precision of McCulloch’s painting. It’s beautifully painted in terms of technique and mood.

However, this show is not specifically about McCulloch or women. The Antigonish artist cites a 2024 Statistics Canada report that one in four girls and one in eight boys have been sexually abused by the age of 18.

This has been born out in the deeply emotional and intense responses she’s received from people when she exhibited at the Mulgrave Roadhouse in Guysborough last summer and now in Halifax. One man walked through the Halifax show and left in tears without speaking to McCulloch who is quietly present at the back of the gallery in case anyone needs to talk.

She recalls the ferocity of a woman who had been abused along with her siblings in the family home declaring this would never happen to her own kids. McCulloch’s painting Triggers, a lush image of amber alcohol, a cut crystal glass and a full ashtray, is about the smells that can trigger memories.

One person told her she has never driven a car and can’t go into a gas station because her family owned a gas station and she was assaulted there by her father and her brothers. She can’t stand the smells.

The early part of this exhibit – divided into four sections of Prey, Predator, Survivor and Blossom – is disturbing and very thorough as a societal look at trauma and sexual assault.

The Prey section includes three small portraits in dark tones of a helmeted combat soldier, a female rape victim and an abused child in distress with their hands over their bent heads. Children Hiding is a scary painting of children hiding in an attic, in a tree with a blanket, in a car with a woman, all in darkness with the light focussed on men partying inside the house.

The Predator section includes Party Predator, an image of a man, back to the viewer, holding two bottles and standing at the top of the stairs. The architecture and the light make this image very sinister.

King of His Castle immediately brings to mind recent news stories in Canada about powerful, uber-wealthy businessmen charged with sexually assaulting young women. A man sits enthroned with his submissive wife and child next to him and the painting is in the lush reds of wealth and power.

McCulloch thought of Reteah Parsons as she painted her image of a woman’s face with arrows coming in from the painting’s sides, each with a familiar saying that shuts down victims: “boys will be boys;” “she is an unreliable witness,” “no one will believe you,” “did you lead him on?,” “were you drinking?,” “what were you wearing?.”

She calls these her angry paintings. “Why does the justice system not have one in four predators in jail? Reteah Parsons took her own life, I’m sure many have done the same.”

As she researched images for paintings about boys’ early exposure to weapons as toys and to male-on-female violence, what she saw on the internet horrifed her. She saw a picture of a two-year-old with a toy rocket launcher truck. She had to go to comicbooks and graphic novels for images for the Sex Education painting because the internet imagery was too terrifying and repulsive.

McCulloch brings striking skill and beauty to fierce images of spikey phallic objects, with inspirations from seed pods to Spanish door handles, in the scratch board series, The Devil’s Fork, and again in the black and white scratchboard Rape. This depicts a circle of exquisitely-drawn, ornately-handled silver forks. The forks’ prongs meet in the centre at a red cutout intended to represent soft, vulnerable tissue.

“If you’re raped,” she says, “it’s like being stabbed in a very intimate place. I’m trying to get that across to young men. A lot of people think rape is sex but it’s traumatizing and terrorizing. It’s a wound you can’t see but that person is carrying that fear and pain.”

The sun starts to come out slowly in the Survivor section where McCulloch balances paintings of happy childhood memories with negative fearful images. The Little Dutch Doll, a sweet painting of a blond doll in a box with china and wooden shoes, is of a beloved doll McCulloch had as a girl. “Hopefully these joyful memories will balance out the dark ones. I think they do.”

She says Talk It Out It, a landscape in light and dark of two men conversing on a walk, is one of the most important paintings to her because talking out trauma is key to survival. “Some people dance it out or write songs. I’m painting it out. You just have to get it out. Counselling is very important; any kind of counselling you can get, whatever works for you. Many people, many people helped me. “

Nature is very important to McCulloch; she finds calm and safety in her Antigonish garden and in walking in nature. Uncomplicated Relationships is a beautiful painting of a lively happy dog’s face because, as she says, some people find it hard to love other people but they can find love in animals.

I Will Defend Myself, both tongue-in-cheek and practical, is a series of oil on panel paintings, all in different sizes, of objects that can be used in self-defense from a china platter to garden shears, from a rolling pin to a frying pan. McCulloch took Aikido. “I felt stronger in the world and that’s so important.”

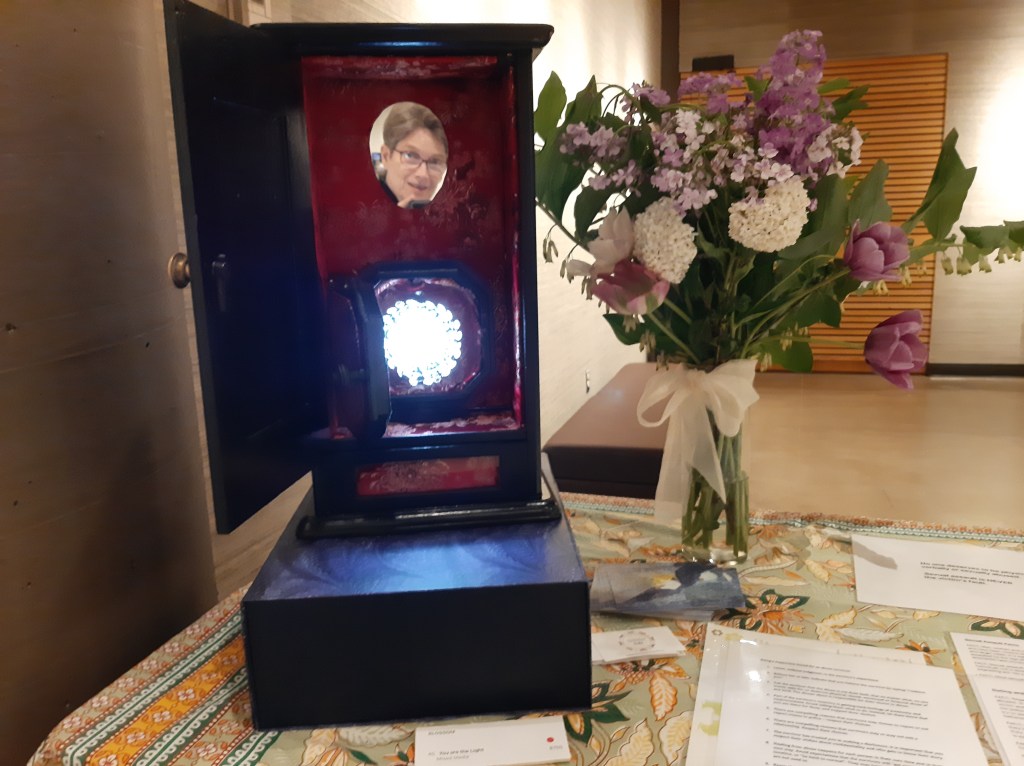

The show ends on a high note with Nipped in the Bud/Bloom Regardless paintings echoing back to the first image. Inspired by the remarkable nature she saw on a trip to Costa Rica she twins a small painting of a bud next to a painting of a beautiful blooming flower. At the very end along with information pamphlets is the innovative box, You are the Light, Open your Heart, with two little doors, a blaze of light and a mirror that lets people know they are loved and they are strong.

Nipped in the Bud: Healing from Childhood Sexual Trauma is at the Chase Gallery, Nova Scotia Archives, 6016 University Ave., corner of University and Robie St., Halifax, to June 28, open Monday to Friday 8.30 to 4.30; Wednesday, 8:30 to 8 p.m.; Saturday, 10 to 3.

McCulloch’s four-page catalogue features quotes by author Dr. Judith L. Herman and Nova Scotia sexual survivor and sexual violence victim advocate Bob Martin, both of whom she finds inspirational.

Dr. Judith L. Herman: “Rape is systemic. Like all systems of brutality it does not exist merely because of its most direct actors. It depends on a healthy host body of people willing to look away.”

Categories: Uncategorized

Tags: antigonish, Art, exhibition, gillian-mcculloch, nova-scotia, painting, paintings, sexual-assault-survivor